State of Mind were honoured to present at the recent Greater Manchester Suicide Prevention Conference alongside Professor Louis Appleby

Former Super League star Danny Sculthorpe, opened up about his battle with depression and the torment that led him to want to end his life.

Speaking at a suicide prevention conference (4th November) that brought together health and social care experts from across Greater Manchester, the ex-prop for England and Wigan explained how his life spiraled out of control after a serious back injury that not only ended his sporting career, but left him bed-bound for months.

During the event – which was run to hear personal experiences and look at how new ways of joined up working can help with preventing suicide – Danny explained how he had bottled up his feelings until he reached crisis point, but was saved by talking through his anguish.

“I’d gone from being this fit, sportsman at the peak of my career, to becoming someone who just moved from a bed to a settee because of the damage done to my back,” he says.

“The depression was crippling. But it wasn’t depression mainly about my career – it was feeling like I couldn’t provide for my wife and kids. Of course I missed the banter and the friendship with the lads, but not being able to provide for my own was the worst thing – especially when we lost the house.”

At that time, in 2010, the young dad-of-two had daughter, Ellie, then aged four and Louis, two. “I just couldn’t get the thoughts out of my head,” he continues. “It was torture feeling like I had let them down. And, like a lot of blokes I didn’t want to talk about my problems.”

Once Danny was able to walk again he still faced the effects of depression, to the point where he had enough tablets to ‘kill 100 people’ which he planned to take in his car. “It was only when my parents asked me what was wrong and what had changed my personality that the floodgates opened,” he says.

In fact, Danny credits that those two questions with saving his life. “I was able to tell my parents everything and that started the process of healing for me. I found that talking was as much an anti-depressant as the drugs.”

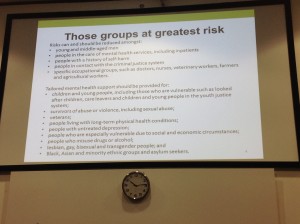

Danny now wants experts across Greater Manchester to listen to his experience while they discuss new approaches to a tragedy that is estimated to claim around 270 lives in the region each year. Each suicide is also thought to affect between 6 and 60 loved ones and relatives.

“My message is simple,” he says. “Devolution broke down barriers – but that’s what talking does too. I’d like to see more people to have the courage to ask someone who is suffering, what’s wrong. That one question could save a life – it did for me.

“People shouldn’t be scared for talking – if someone is suicidal, asking a question isn’t going to make them worse – they have already got to that point.”

Danny, now 37, spends his time talking to youngsters about the power of talking and words. He is also about to start a new career as he trains to be a counsellor.

“I think I’d have more impact on people because I have lived through the experience. I’d definitely like to see more counsellors and other advisors who have overcome depression, because unless you have been through it, you can’t imagine how bad it is.”

Today, Danny is optimistic about the future – but wants more people in Greater Manchester to have that second chance. He also wants to advocate for the power of exercise in helping to relieve stress and low mood.

“I will never be able to go back to rugby, but I now box instead,” he says. “I get an endorphin rush from working out, having a shower and then sitting down with my family for tea. I think more exercise on prescription is a very strong part of any mental health treatment.”

On a wider level, he sees society as having the ultimate effect on helping to prevent suicide – which claims the lives 13 young men – an entire rugby league team – across the country each day.

“You don’t have to be on a field playing rugby to be part of a team,” he explains. “We are all part of a team every day and if someone looks seriously depressed, ask them how they are. It could save their life.”